“The Candy Man”: The Texas Halloween poisoning of 1974 — what really happened

On Halloween night, October 31, 1974, eight-year-old Timothy O’Bryan of Deer Park/Pasadena, Texas, died less than an hour after tasting a “Giant Pixy Stix.” Investigators soon concluded the candy had been laced with potassium cyanide by his father, Ronald Clark O’Bryan, in a scheme to collect life-insurance money. The case horrified the country and cemented a popular fear about “poisoned Halloween candy,” even though it was not a random attack by a stranger.

The people and pressures behind the crime

Ronald O’Bryan was a 30-year-old optician with mounting debts and a faltering work history. In 1974 he earned about $150 a week and was behind on loans and car payments. In the months leading up to Halloween he quietly stacked multiple life-insurance policies on his two children—$10,000 policies tied to a bank club and additional $20,000 policies on each child taken out in late September/early October—while carrying little or no insurance on himself.

O’Bryan had also been asking around about cyanide. Colleagues and a friend from a chemical company later testified he’d discussed fatal dosages, and a Houston scientific supplier remembered O’Bryan inquiring about buying cyanide (he balked when told the smallest container was five pounds).

Halloween night: five Pixy Stix

Despite rain on October 31, O’Bryan took his two children trick-or-treating with a neighbor, Jim Bates, and Bates’s two kids. At one darkened house where no one came to the door, the children ran ahead; O’Bryan later rejoined the group holding five long Pixy Stix, claiming the occupant had answered late and handed them out. He distributed one to each of the four children and gave the fifth to a boy from his church. That night Timothy asked for candy before bed; the Pixy Stix tasted bitter, and within minutes he began vomiting and convulsing. He died en route to the hospital.

An autopsy quickly confirmed cyanide. Police retrieved the remaining four Pixy Stix before any other child ate them. (A Washington Post report noted prosecutors said O’Bryan had “spike[d] five 22-inch plastic tubes,” and only Timothy consumed his.)

From “mystery neighbor” to prime suspect

At first O’Bryan said he couldn’t recall the exact house. Under pressure, he pointed police to the darkened home of Courtney Melvin, an air-traffic controller. But Melvin had been at work until nearly 11 p.m., and more than 200 witnesses corroborated the alibi; the Melvin family had stopped answering the door when they ran out of candy early in the evening and had never seen O’Bryan or Bates that night. Investigators’ focus swung decisively back to O’Bryan.

Several other facts tightened the net. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals summarized extensive evidence of premeditation and motive: the fresh policies on the children, O’Bryan’s search for cyanide sources, and even his calls to an insurer and bank the morning after Timothy’s death asking how to collect. The court also emphasized that O’Bryan handed out four additional poisoned sticks—his daughter, two neighbor children, and another child from church—to disguise the targeted murder of his son as a random Halloween poisoning.

Trial, conviction, and execution

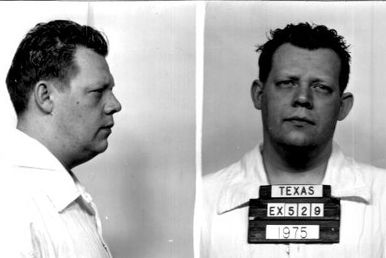

O’Bryan was arrested on November 5, 1974, indicted for capital murder and four counts of attempted murder, and tried in Houston in May–June 1975. The jury deliberated only minutes before convicting and sentencing him to death. On appeal in 1979, Texas’s high criminal court affirmed, detailing the calculated nature of the offense and O’Bryan’s efforts to frame an innocent neighbor. Federal courts later denied habeas relief.

After last-minute appeals failed, O’Bryan was executed by lethal injection in Huntsville in the early hours of March 31, 1984 (Texas Department of Criminal Justice records date the execution as March 30, reflecting administrative timing; contemporary reporting places the injections just after midnight).

Forensics note: the cyanide and the candy

The Harris County medical examiner’s office determined cyanide in the Pixy Stix and in Timothy’s body; Texas appellate records also describe O’Bryan’s months-long curiosity about cyanide sources and lethal doses. Contemporary coverage and later summaries describe the “Giant Pixy Stix” as long plastic tubes of powdered candy that had been opened, refilled near the top with cyanide, and resealed—a ruse that fooled a child but drew no attention at the door.

What the case did—and didn’t—prove about Halloween candy

The “Candy Man” killing helped ignite and then perpetuate the dread of anonymous Halloween poisoners. Yet sociologist Joel Best, who has tracked “Halloween sadism” reports since the 1980s, has never found a verified case of a child killed or seriously hurt by a randomly distributed, tampered trick-or-treat candy. Where deaths were initially blamed on “poisoned candy,” investigations have traced them to unrelated causes, accidents, hoaxes—or, as in Texas in 1974, a family member committing murder. O’Bryan’s crime, in other words, was real and monstrous, but it was not the urban-legend scenario of a stranger targeting random kids.

Key dates

Oct 31, 1974: Timothy O’Bryan dies after ingesting cyanide from a Pixy Stix given by his father during trick-or-treating.

Nov 5, 1974: Ronald O’Bryan is arrested; later indicted for capital murder and attempted murders.

June 3, 1975: Jury convicts and sentences O’Bryan to death.

Sept 26, 1979: Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirms conviction and sentence.

Mar 31, 1984 (early a.m.): O’Bryan executed in Huntsville after final appeals fail. (TDCJ lists Mar 30; contemporaneous reporting places execution just after midnight Mar 31.)

Sources & further reading

O’Bryan v. State, 591 S.W.2d 464 (Tex. Crim. App. 1979) — appellate opinion summarizing evidence of motive, planning (insurance), and cyanide inquiries.

Texas Dept. of Criminal Justice — death-row record and last statement of Ronald C. O’Bryan.

Washington Post (Mar. 31, 1984) — contemporaneous report on execution and trial highlights.

Justia/Law Resource federal appeals — habeas decisions referencing the case history.

KPRC-TV trial footage (Texas Archive of the Moving Image) — local TV coverage from 1975.

Court record refuting the “mystery neighbor” — testimony clearing homeowner Courtney Melvin.

Joel Best, University of Delaware — scholarship debunking “poisoned Halloween candy” urban legends.

Bottom line

The “Candy Man” killing was a calculated filicide for insurance money, disguised as a random Halloween poisoning by handing out additional tainted candies. It became a cautionary tale that changed how many parents think about trick-or-treating, but the broader fear of anonymous poisoners has not been borne out by evidence.

Leave a comment